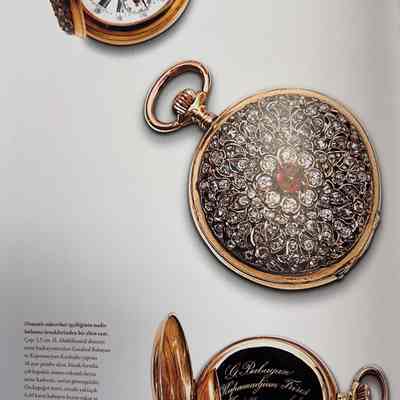

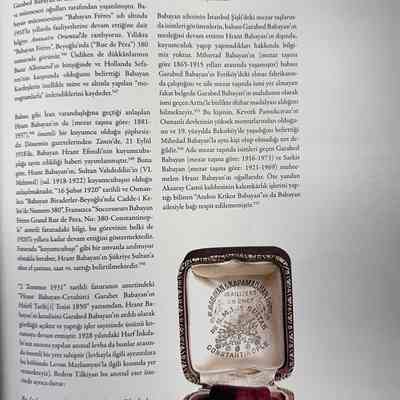

Pocket Watch (G. Babayan, Kapamagjian)

Name/Title

Pocket Watch (G. Babayan, Kapamagjian)Description

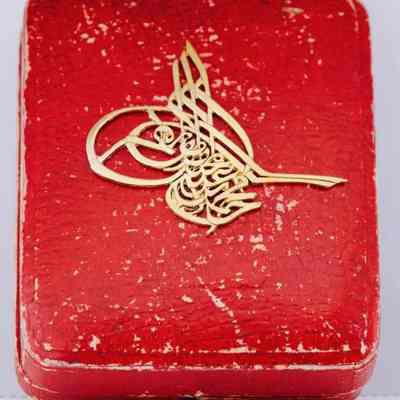

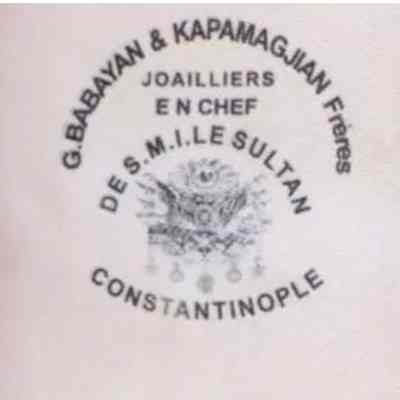

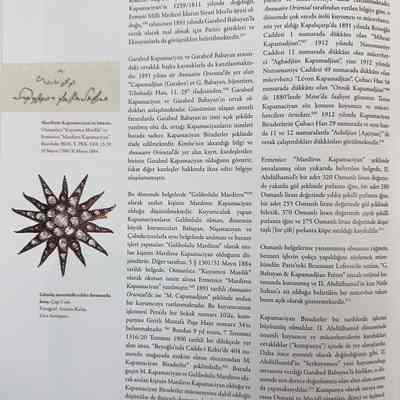

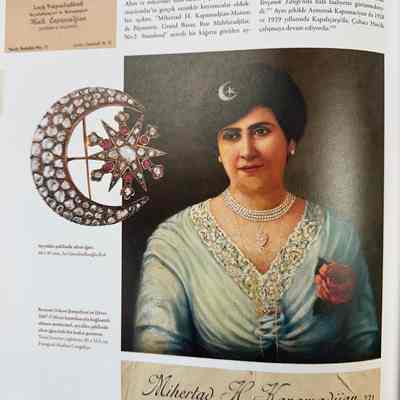

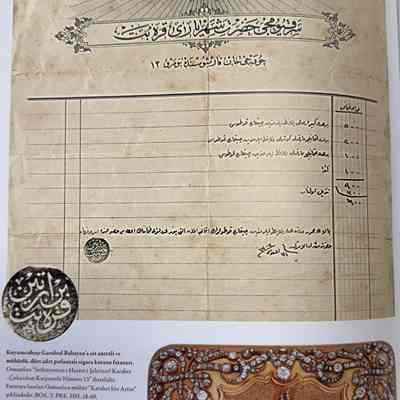

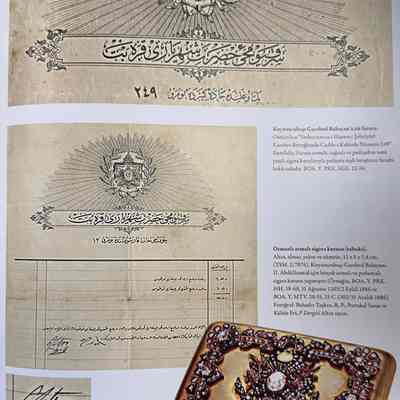

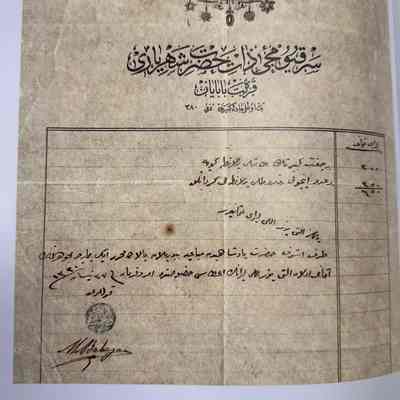

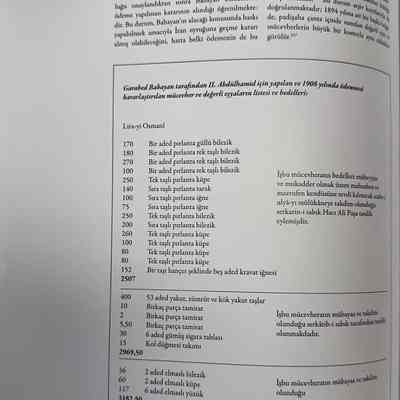

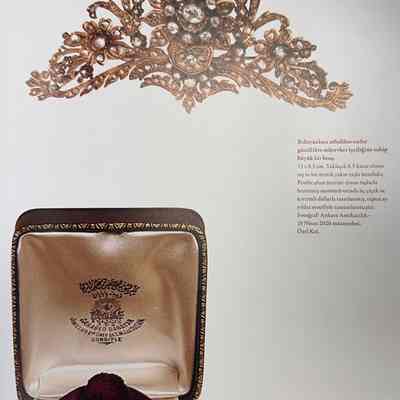

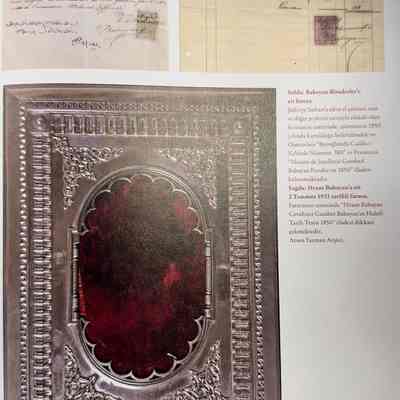

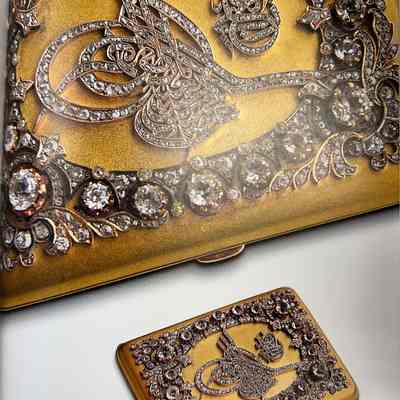

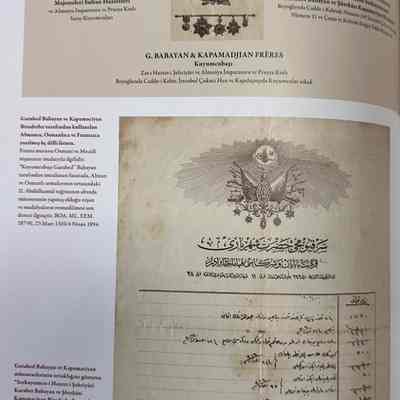

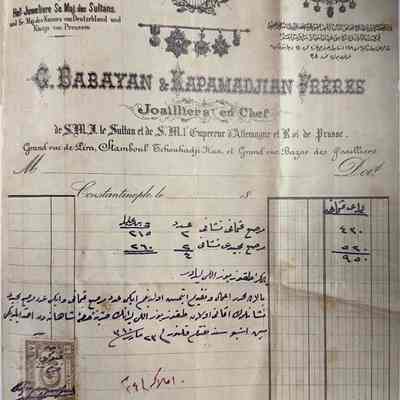

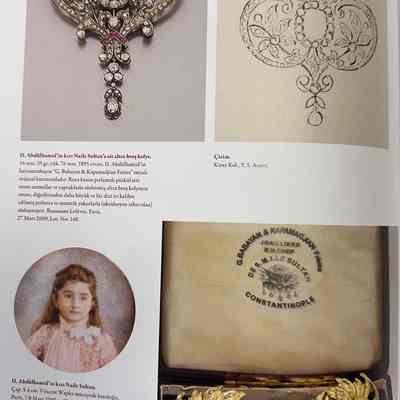

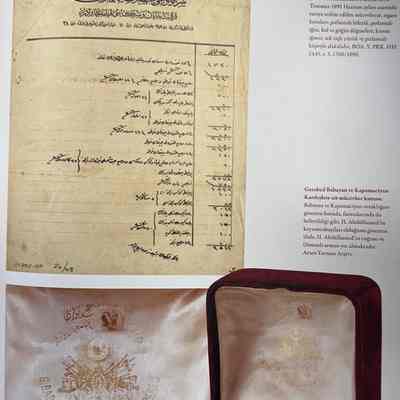

14k gold pocket watch made by G. Babayan and Kapamagjian Freres who were the chief jewelers of the Sultan. According to the listing, the pocket watch was made circa 1870s. It features a fine gold dial with Ottoman numerals and original hands. The movement is fully hand-finished, including an anchor escapement, ruby endstone, and full jeweling, and remains in working order. It includes a hand painted picture of the Blue Mosque(?). The watch is housed in its original red Moroccan leather presentation case, adorned with the Sultan’s personal tughra cypher. The full names of the partners are Garabed Babayan and Mardiros Kapamagjian. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Garabed Babayan had established himself as one of the most renowned jewelers of the Ottoman Empire. His name appears in multiple official records, confirming his long-standing association with the palace and his extensive commissions for Sultan Abdulhamid II. Among these records is an 1887 transaction detailing substantial payments—600 Ottoman liras for a custom-made jewelry box, 500 Ottoman liras for a large diamond, and 200 Ottoman liras for another diamond piece—demonstrating Babayan’s role as one of the empire’s most trusted jewelers. His status was further cemented in 1879 when he was officially recognized with the title "Serkuyumcu" (Head Jeweler) to the Sultan. His workshop, located in Beyoğlu, was registered under the prestigious title "Serkuyumcu-i Hazret-i Şehriyari Karabet"—translated as "Karabet, Head Jeweler of His Imperial Majesty". Over the years, Babayan’s reputation extended beyond the Ottoman court. By 1885, he had begun conducting high-profile transactions, including a significant jewelry sale to the Russian Tsar and his wife, solidifying his influence on an international scale. During this period of prosperity, Garabed Babayan formed a strategic partnership with Garabed Kapamaciyan, another distinguished Armenian jeweler. Kapamaciyan, originally from Gallipoli, was born in 1811 and was an active member of the Armenian National Center’s Political Assembly. Records indicate that in 1891, both Babayan and Kapamaciyan traveled to Paris, likely in search of exclusive materials and clients, and met with members of the prominent Eknayan family, who were influential in the European jewelry market. Their collaboration is well-documented. The 1891 edition of Annuaire Oriental lists their business as "Capamadjian (Garabet) et G. Babayan, bijoutier", confirming their joint operations in the jewelry trade. Invoices and historical documents frequently mention Babayan’s name, further attesting to the depth of their business relationship. In Ottoman records, Kapamaciyan is sometimes referred to as “Mardiros from Gallipoli”, but in Armenian records, his full name appears as "Mardiros Kapamaciyan". The Annuaire Oriental of 1891 also records him as “M. Capamadjian”, underscoring his recognized presence in the industry. While Babayan’s expertise and influence lay in his imperial commissions, the Kapamaciyan family was renowned for their craftsmanship. More than just traders, the Kapamaciyans were true artisans, as evidenced by a business letterhead bearing the name "Mihrétad H. Kapamadjian - Maison de Bijouterie, Grand Bazar, Rue Mahfazadjilar, No 2 - Stamboul." This indicates that, alongside Babayan, they maintained a prestigious jewelry house in the heart of Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar, supplying fine jewelry to elite clients. Despite their prominence, the turn of the 20th century brought challenges. Babayan’s role as the court jeweler began to decline, and by the early 1900s, his exclusive position as the Sultan’s jeweler had weakened. One of the last records of his commissions dates to 1908, when payments for palace jewelry purchases were delayed—perhaps a sign of the empire’s growing financial and political instability. By 1912, competition among Armenian jewelers intensified, with names like Şadyoryan rising in prominence. While Babayan’s name continued to appear in legal and financial documents, by the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, his legacy as a leading jeweler had largely faded into history. However, the Kapamaciyan family persevered. Historical records indicate that they continued producing jewelry well into the 1920s, and by 1928, they were still actively operating. Their craftsmanship and reputation endured beyond Babayan’s decline, ensuring that their name remained synonymous with Ottoman-era luxury and fine jewelry.Item Type

WatchCategory

Watches