Label

Label from 2014.Art for Social Change:

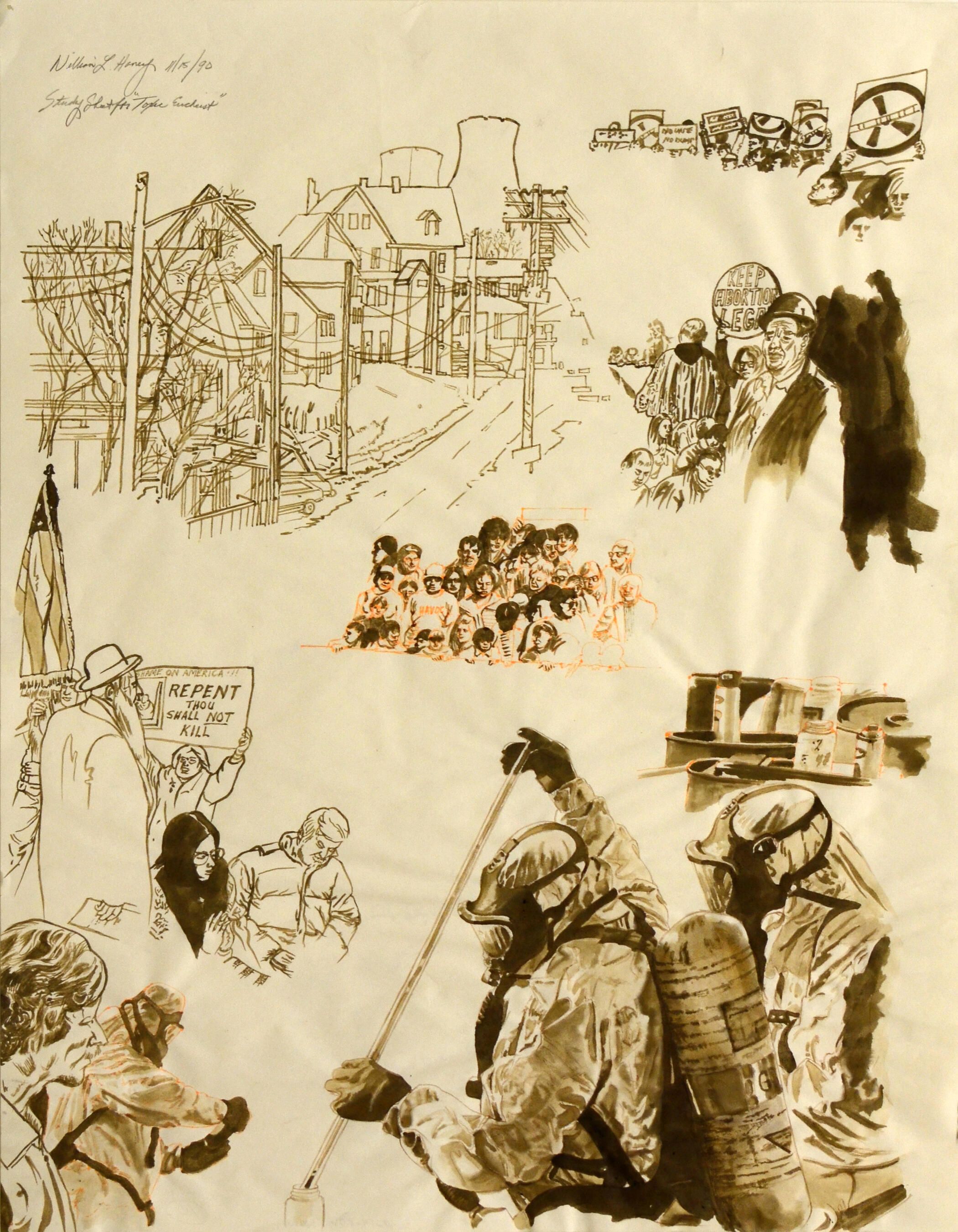

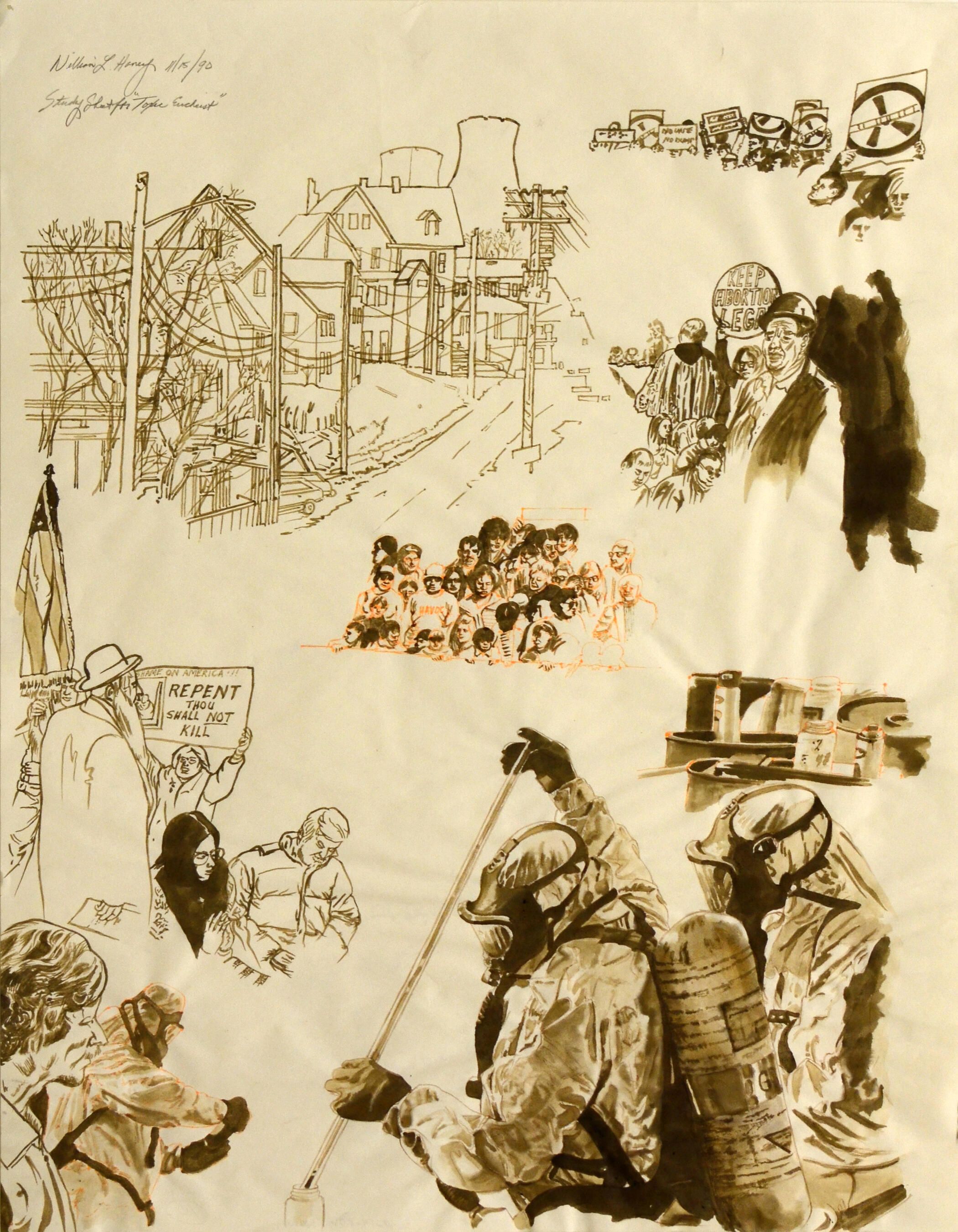

Like many of his works, Topeka native William Haney’s Study for a Toxic Eucharist examines the social and political conflicts of contemporary American life. In it we see a town in the shadow of a nuclear power plant, a demonstration against nuclear power, pro-life and pro-choice protestors, a priest, an orthodox Jew, oil barrels and men in hazmat suits conducting tests. In the middle is a group of people, who, in the watercolor based on this drawing, hold a banner as they march in a demonstration. One person in the group wears a shirt with the word “havoc” on it. Haney’s paintings were not intended to provide answers, but to provoke serious discussions about the issues facing our country.

This drawing is typical of Haney’s process. He often took images from news media and redrew them on separate areas of a sheet of paper. In the final work, in this case a watercolor, the various scenes would be integrated into a single composition. The Mulvane owns approximately 500 works by Haney, donated by his wife, Beverly Haverstock. The museum is thus the largest repository of works by this fine artist.Label

2024, “In This Place: American Dreams”

This drawing by William Haney focuses on prominent political issues in the United States: abortion rights and energy sources impacting the environment. These topics seem like a weird combination at first glance, but they were both the subjects of intense debate when Haney created this work in 1990, and they continue to have relevance today. Protests and counterprotests about abortion and nuclear power are shown alongside imagery of power plant workers and pill bottles. These contrast each other and provoke the onlooker to think about both issues harder and in a different context. I see a connection between these topics and the issue of safety: the physical safety of the employees of nuclear power plants, the health of people who live around power plants, and the physical and mental well-being of people undergoing abortions as well as people who cannot get abortions.

—Kamryn Dollahon, Washburn University studentLabel

2024, "Beyond the Iron Curtain: Visions from the Cold War"

In the wake of the Cold War, the world was shrouded in fear and uncertainty. The government promised a brilliant future of nuclear power, the church promised peace and love for all. But in Study for Toxic Eucharist, Haney depicts multiple protests about nuclear power and abortion rights. To the left, we see a quaint townscape with a nuclear power plant in the background. Below that, we can see a religious leader spearheading an abortion protest. Eucharist, also known as communion, is the ritual consumption of consecrated bread and wine, representing the body and blood of Jesus in the Christian faith. Nuclear power was feared for the toxic byproducts that could harm the community. Both religion and nuclear power have an ambiguous essence that, when combined, kindle the fear of the unknown. Is Haney suggesting that the things that promise the best for humanity also bring forth its worst traits?

Text by Alli Lane, Washburn student